© Colin Low 2000

When human beings try to dream up a model of reality, they rarely go far from what is generally known. When we communicate, we have to use what we share. It has been said that medieval cosmogonies were inspired by the court hierarchy of the late Roman Empire – the Emperor or Empress at the summit, and widening rings of court officials with more and more bizarre titles, mirrored in the Celestial Hierarchies of the Neoplatonist pseudo-Dionysus, which in turn became the basis for Dante’s The Divine Comedy.

It is certainly the case that in Kabbalah a wide range of commonplace descriptive metaphors are used – seas, fountains, and rivers; the human body; conjugal relations between man and woman; the halls and gates of a king’s palace; a king and his subjects; a mother bird and her chicks; these are only a few examples. This rich seam of metaphor and allegory is part of the beauty of Kabbalah. A beginner can grasp these metaphors at an intuitive level, and they continue to yield meaning after many years of contemplation.

The ship narrative is one of the oldest literary forms. From the legend of Jason and the Argonauts to the Mutiny on the Bounty to StarTrek, writers have used the ship as a social microcosm. Much of the attraction of the ship narrative is its boundedness, the close physical proximity of its protagonists combined with a rigid social hierarchy. The ship is a closed community, an island universe of souls who survive against the odds in a hostile environment. The ship "boldly goes" into the unknown, and survives because its crew sacrifice their freedom and a large part of their individuality in order to carry out formal roles essential to the survival of the community.

The ship is interesting as a metaphor because it is both One and Many. Seen from the outside it is One. It has to be One because the outside is hostile, inimical to human life. Seen from the inside it is Many, human beings trying to live their lives as individuals while constrained by the hierarchy and discipline necessary to confront a hostile environment. Many forms of human organisation conform to this pattern in varying degrees, and there is much in common between the ship and the all-pervasive modern corporation riding out the storms of the market and attacks by competitors.

Kabbalah also attempts to reconcile the ideas of the One and the Many, the unity of God and the diversity of the creation. When the divine order of the creation is contrasted with the malevolent and chaotic realms of the qlippoth, links with the ship narrative become apparent. The creation myth of Sumer and Akkad, one of the earliest literary myths in our possession, tells of the victory of a creator god against the chaotic powers of the deeps. This myth lingers in the creation story of Genesis, and has found its way with Kabbalah with little loss of mythical intensity. The deeps (tehom), the waters that God separated, remain as a symbol of the hostile and chaotic powers that threaten the integrity of the creation.

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life can be viewed as a model of organism and governance. Viewed as an organism it is often shown superimposed on the human body, emphasising how the spheres underpin the dynamics and functioning of a living thing. As a model of governance it employs the oldest metaphor for governance, that of kingship. At its heart (Tipheret) is the King. His crown is Kether, and his sword and sceptre are Gevurah and Chesed, the two primary aspects of leadership which stand traditionally for mercy and severity. His martial hosts are Hod and Netzach (hence the divine name Tzabaot) and the kingdom is Malkuth. The King is the One, and his subjects are the Many. When the Kabbalah began, the King with his subjects was the most pervasive form of collective human organisation.

To explore this idea of organism and governance further, I have chosen to look at one of the most popular contemporary ship narratives, the voyages of the U.S.S. Enterprise, as told in the television series Star Trek - The Next Generation. This is a useful example because most people have seen episodes and are familiar with the crew, their roles and their characters. They are more familiar today than the Greek, Roman or Egyptian pantheons of gods and goddesses, and the Star Trek script writers have clearly been inspired by the usual archetypes. Like most soap operas Star Trek attempts to address contemporary social issues - cultural diversity, variant sexual customs, non-interference and self determinism, core moral and ethical issues and so on. Whether it succeeds is largely irrelevant - emulating a lowbrow Plato, its dialogues are as close to a challenging ethical debate as many children are likely to receive.

From an external point of view, the Enterprise functions like a simple organism. It moves from place to place. It has a wide range of sensors, and interacts with its environment. It responds in a complex manner to approaches and threats, even to the extent of defending itself with deadly force.

The Enterprise behaves like this because a complex structure of formal roles, regulations, and discipline (governance) results in a crew that works together, and the entertainment value in a large proportion of episodes is watching how the crew achieve and maintain this cohesion in the face of problems that are often life-threatening.

It is possible to assign leading members of the crew to sephiroth on the Tree of Life, just as people have assigned planets, gods and goddesses from various pantheons, colours etc.

There may be some who find this trivialises a deep subject, but in response I will say that metaphors are the creations of human beings. We have no more license to worship our favourite metaphors, however ancient and revered, than we do to worship graven images. Kabbalah has always employed intuitive metaphors, and Star Trek is as good a place to look for metaphors as any other.

Malkuth is the Enterprise and her

crew.

Malkuth is the Enterprise and her

crew.

The man in charge of the machinery of the universe is Chief Engineer Geordi

LaForge. He is blind (like the demiurge Ialdebaoth/Samael in gnostic myth) and so his

vision is augmented using an implant.

The man in charge of the machinery of the universe is Chief Engineer Geordi

LaForge. He is blind (like the demiurge Ialdebaoth/Samael in gnostic myth) and so his

vision is augmented using an implant.

The android Data is the essence of unemotional intellect. Although

human-created, he is officially recognised as an autonomous life form with full legal

privileges. Data yearns for human experience, laughter, feeling, and irrationality.

According to purely logical and rational criteria he is superhuman, and yet we suspect

that if he was genuinely rational, he would be incapable of acting ethically, and perhaps

even of reaching any kind of decision - if you don’t know what you want, you

don’t get it.

The android Data is the essence of unemotional intellect. Although

human-created, he is officially recognised as an autonomous life form with full legal

privileges. Data yearns for human experience, laughter, feeling, and irrationality.

According to purely logical and rational criteria he is superhuman, and yet we suspect

that if he was genuinely rational, he would be incapable of acting ethically, and perhaps

even of reaching any kind of decision - if you don’t know what you want, you

don’t get it.

Data shares Hod with Dr. Beverley Crusher, the Chief Medical Officer.

Medicine has reached the level where it is more akin to bio-engineering, and Dr. Crusher

is a highly skilled technical specialist usually seen wielding a battery of diagnostic

instruments.

Data shares Hod with Dr. Beverley Crusher, the Chief Medical Officer.

Medicine has reached the level where it is more akin to bio-engineering, and Dr. Crusher

is a highly skilled technical specialist usually seen wielding a battery of diagnostic

instruments.

Deanna Troi is the ship’s counsellor, the Starfleet equivalent of

Inhuman Resources. She is a Betazoid and an empath, which means she is forever sensing

people’s moods. The series gives her license to wear spray-on clothing, which hides

nothing of her generous figure. By coincidence, the actress who plays the part is called

Marina Sirtis, and she invariably gives the impression of Venus newly arisen from the

Cypriot surf.

Deanna Troi is the ship’s counsellor, the Starfleet equivalent of

Inhuman Resources. She is a Betazoid and an empath, which means she is forever sensing

people’s moods. The series gives her license to wear spray-on clothing, which hides

nothing of her generous figure. By coincidence, the actress who plays the part is called

Marina Sirtis, and she invariably gives the impression of Venus newly arisen from the

Cypriot surf.

The picture on the right confirms the general impression.

The heart of the Enterprise is the bridge, and hence I have used a picture

of the main characters posed in the bridge. The photo used is unusual in that it is one of

the few group photos that contains Guinan.

The heart of the Enterprise is the bridge, and hence I have used a picture

of the main characters posed in the bridge. The photo used is unusual in that it is one of

the few group photos that contains Guinan.

The crew member that approximates to Tiphereth is Riker. Riker is the ship’s First Officer, and the First Officer is at the heart of a ship, normally responsible for the day-to-day running and operational integrity of a ship. Jonathon Frakes, who plays Riker, has a difficult role because the attention to administrative detail required in the First Officer role - duty rosters, repairs, staff problems, etc - tends not to be visible in a 60 minute format, and so he is depicted as the general purpose, superbly competent all-good guy forever in Picard’s shadow.

In many ways it would be appropriate to place Picard at the heart of the ship, but no other ship’s officer could take his place in Chesed.

Worf is the Security Officer. A Klingon, steeped in the rituals of Klingon

militancy and violence, Worf is controlled to the point of having difficulty with

emotional relationships.

Worf is the Security Officer. A Klingon, steeped in the rituals of Klingon

militancy and violence, Worf is controlled to the point of having difficulty with

emotional relationships.

Worf is a brilliant depiction of Gevurah. His dominating motivations are duty and honour, so his behaviour is tightly constrained by whatever he considers to be dutiful and honourable. He is not afraid to die upholding duty and honour and exhibits something close to a death urge - he would make a good Kamikaze. He is intensely conservative and protective of the Enterprise - his advise to Picard can frequently be parodied by the famous saying made by the Papal Legate during the Cathar crusade: "Kill them all - God will know his own".

Despite the violence simmering below the surface, Worf bottles his feelings and rarely gives way to emotion.

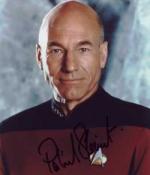

Jean Luc Picard embodies authority. Controlled and decisive, his motivation

at all times is to "do the right thing", and so he is usually at the centre of

the various ethical dilemmas that the crew are required to solve.

Jean Luc Picard embodies authority. Controlled and decisive, his motivation

at all times is to "do the right thing", and so he is usually at the centre of

the various ethical dilemmas that the crew are required to solve.

Picard does not manage by consensus. Something that the actor Patrick Stewart portrays effectively is an unquestionable sense of authority, an intimidating sense of authority. There is never the slightest doubt who is in charge of the Enterprise.

Picard is not the jovial type. He tends to be snappish, intense, often ill-tempered, but this rarely intrudes on his decision making or concern for the welfare of the crew. This concern extends beyond the crew and can be characterised by an altruistic humanism, a belief that the common good has to be actively upheld, fought for, and its formative principles should not be sacrificed by expedient decision making.

Guinan is a woman shrouded in mystery. When the plot demands it, she plays

the role of mother to the crew, and even Picard goes to her for advice. She is one of his

very few confidants.

Guinan is a woman shrouded in mystery. When the plot demands it, she plays

the role of mother to the crew, and even Picard goes to her for advice. She is one of his

very few confidants.

She is old - centuries old - and due to a bizarre temporal happenstance she comes from the distant past. Her race was destroyed by the Borg, a circumstance that recalls the destroyed worlds of the Kings of Edom in the Zohar.

Binah is also represented by the Federation Directives, a binding set of principles

used to regulate the behaviour of the ship’s crew. The best known is the Prime

Directive which covers non-interference with other life forms, but there are a couple of

dozen others.

It is difficult to provide good symbols for Chokhmah, but I have chosen the

seal of the United Federation of Planets. If there is anything that empowers the Enterprise

to "boldly go", it is this.

It is difficult to provide good symbols for Chokhmah, but I have chosen the

seal of the United Federation of Planets. If there is anything that empowers the Enterprise

to "boldly go", it is this.

Text and Tree composition © Colin Low. I am grateful to the many StarTrek WWW

sites from which I have gleaned pictures, and hope the copyright holders will consider my

use of their material fair and appropriate.