|

|

|

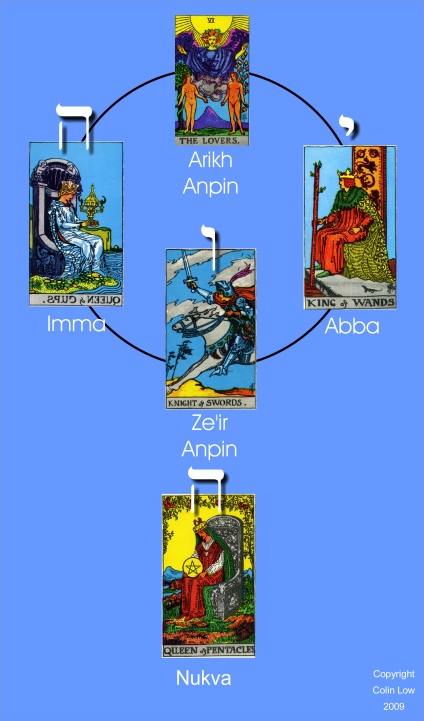

Partzufim Partzuf means a face or visage; it is sometimes translated as countenance, persona or personality or configuration, but probably the most accurate modern translation would be adopt the terminology of the Swiss psychologist C.G. Jung and and translate it as "divine archetype". A simple way to describe the Partzufim is to imagine that each letter in the Tetragrammaton, the divine name of four letters, is a living thing in its own right. This is the strangest idea to keep in one's head while still recalling the fundamental monism of Judaism. Each Hebrew letter in YHVH is an irreducible part of the whole, but each letter has its own life in respect of its relationship to the other letters. It is tempting to relate this to organs in the body. We know that although the heart, the lungs, the liver, the blood, and the reproductive organs cannot function in isolation, they have distinct roles to play and have their own internal relationships. However appealing this simile might seem, it is too simple. The Partzufim are complete living configurations of divine energy, and it comes as something of a shock and a surprise to discover that one of the five Partzufim, Ze'ir Anpin, is also the Holy One, Blessed Be He, the God of Abraham, Isaac and Moses, the God of the Bible. As it happens, this is one of the least of the surprises the uninitiated is likely to experience, as one encounters the sexual imagery used to describe the dynamics of this nuclear family. Put simply, there is a Father and a Mother whose continuous sexual coupling produces a Son and a Daughter. The Daughter is also a Mother (mother to all life as it happens), and the flow of divine grace and blessing to all of creation depends on the sexual relationship between the Son and the Daughter, who are usually called the King and the Queen. When they embrace, blessings flow into the world. When they turn away from each other, the dark side gains power over the world. A basis for this imagery is one of the most frequently quoted source texts in Kabbalah, The Song of Songs. This ancient text appears to be a celebration of the pleasures of physical love between a man and a woman, and it may well have been that, but its traditional interpretation is as an allegory of the relationship between God and Israel. The early Christian Church Fathers were quick to take notice of it, and Origen (185-254 CE) wrote a commentary on it. Its popularity continued into the Middle Ages, and prominent churchmen such as St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153 CE) wrote extensive sermons on it from the perspective of the spiritual relationship between a Christian (i.e. himself) and Christ. The modern reader might be startled by the hermeneutic convolutions necessary to shoehorn personal spirituality into the format of an erotic love poem. It is against this background of fierce asceticism and spiritual eroticism, and at approximately the same time period, that we can place the emergence of Kabbalah. The Song of Songs is quoted in another of the seminal source texts for Kabbalah, the Shi'ur Komah - The Measure of the Body. The Shi'ur Komah describes a vision of God seated on the throne of glory in the company of the angel Metatron and various spiritual inhabitants of Heaven. It enumerates the parts of the divine body and gives their measure and secret names in dimensions of incomprehensible and possibly nonsensical vastness. The vision of God on the Throne of Glory owes much to descriptions of the heavenly throne in the Bible, especially Isaiah and Daniel. The Shi'ur Komah connects the King and lover in the Song of Songs with the cosmic figure in the throne, and it is from this improbable fusion of images that we can begin to comprehend the anthropomorphism of three of the most esoteric books of the Zohar: the Sepher de-Tzeniuta, the Idra Rabba, and the Idra Zuta, collectively known as the Idrot (or "convocations"). It is here that the Partzufim make their appearance. There are two principal Partzufim, Arik Anpin (Vast/Long Face) and Ze'ir Anpin (Short Face). They are often called by the Latin titles from Knorr von Rosenroth's Latin translation of the Idrot, Macroprosopus and Microprosopus. The intention behind the names is to convey the qualities of "forebearing" and "impatient", as Arik Anpin emanates only pure and unadulterated mercy and loving-kindness, whereas Ze'ir Anpin is polarised and emanates the dual qualities of mercy and judgement. Alternative titles for Arik Anpin are Atika Kadisha (the Ancient Holy One) and Atik Yomin (the Ancient of Days). Originally the alternative titles appear to have been used as synonyms, but in time they were used to make subtle distinctions in the level of the primary crystalisation from En Soph. Arik Anpin is (verbally) depicted as a vast head. The Idrot describe the cranium, the brain, hair, the beard, the nose, forehead, cheeks and lips of Arik Anpin in considerable detail. The hair and beard are white and luxurious, and precisely speicified. Vast numbers of worlds depend on the influences emanating from every part of the Great White head. In particular, thirteen streams of pure dew (thirteen aspects of Mercy) descend from Arik Anpin and provide the influx that (how can one express this?) "animates" Ze'ir Anpin. Although there are two eyes, they have the appearence of one, and only the right side (that is, the quality of Mercy) is seen. For this reason Arik Anpin is sometimes depicted as a head seen in profile, the left side being hidden in En Soph. If the eye of Arik Anpin were to close for an instant, the universe would cease to exist. The Idra Zuta includes the partzufim of Father and Mother within the overall description of Arik Anpin. Father and Mother are the external aspect, and the trio together correspond to Keter, Chokhmah and Binah. There is much play with Hebrew spelling and gematria in the Idrot - for example, Chokhmah corresponds to the letter Yod in the Tetragrammaton, Binah to He, and when they are taken together with Ben (son) they make Binah. In other words, Binah is the Mother pregnant with the seed of the Father, and bearing the Son, who is Ze'ir Anpin. This is not a one-off deal. In the timeless eternity of Arik Anpin, Father and Mother couple without cease, the son is perpetually conceived, carried to term, and delivered into independent existence. The son is simultaneously King and couples with his Queen who is also daughter. Ze'ir Anpin is described as a full-bodied male figure. Attention is again focused on the details of his face, hair and beard. Ze'ir Anpin corresponds to the letter vav in the Tetragrammaton and the six sephirot Chesed, Gevurah, Tiferet, Netzach, Hod and Yesod. Ze'ir Anpin embodies the dual qualities of loving-kindness (chesed) and strict judgement (din), giving and holding-back, and also the full executive power of the name YHVH - an aspect of the kabbalistic holographic principle in which every part of the whole is the whole.  The relationship between Ze'ir Anpin and his woman Nukva

is filled with drama. Sometimes they face each other and embrace, and

the worlds are filled with blessings. Sometimes they turn away from

each other, and strict judgement (din) has dominance in the worlds, and the power of the evil shells (klippot) afflicts humanity. Nukva is Bride (Kallah, as in the Song of Songs) and Queen (Malkhah) of the kingdom, which is Malkhut. Her colour is black - "I am black, but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem". She is the personification of the Shekhinah, the immanence of God (or divine presence) in the creation. Some of the symbolism of Ze'ir and Nukva

comes from the Sun and Moon, and shows an understanding of basic

astronomy. The Moon has no light of her own, and is lit by the Sun.

Each month the Sun "withholds" his light and the Moon is darkened. This

is equated to female menstruation, at which time, according to

Jewish law, she is ritually impure and must stay apart (niddah). This complex of analogies is translated into the cosmic realms as an explanation of history: the cosmic Sun, which is Ze'ir Anpin, turns away from the cosmic Moon Nukva,

and she is immersed in a realm of impurity in which evil has the upper

hand. There are deep connections here with the Jewish lunar calendar

and the monthly sanctification of the Moon (Kiddush Levanah). The relationship between Ze'ir Anpin and his woman Nukva

is filled with drama. Sometimes they face each other and embrace, and

the worlds are filled with blessings. Sometimes they turn away from

each other, and strict judgement (din) has dominance in the worlds, and the power of the evil shells (klippot) afflicts humanity. Nukva is Bride (Kallah, as in the Song of Songs) and Queen (Malkhah) of the kingdom, which is Malkhut. Her colour is black - "I am black, but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem". She is the personification of the Shekhinah, the immanence of God (or divine presence) in the creation. Some of the symbolism of Ze'ir and Nukva

comes from the Sun and Moon, and shows an understanding of basic

astronomy. The Moon has no light of her own, and is lit by the Sun.

Each month the Sun "withholds" his light and the Moon is darkened. This

is equated to female menstruation, at which time, according to

Jewish law, she is ritually impure and must stay apart (niddah). This complex of analogies is translated into the cosmic realms as an explanation of history: the cosmic Sun, which is Ze'ir Anpin, turns away from the cosmic Moon Nukva,

and she is immersed in a realm of impurity in which evil has the upper

hand. There are deep connections here with the Jewish lunar calendar

and the monthly sanctification of the Moon (Kiddush Levanah).This outline of the Partzufim as it appears in the Zohar was enormously elaborated by R. Isaac Luria in the sixteenth century. The dramatic features were exaggerated. Some scholars have attributed this to the trauma of the Spanish expulsion (1492), as an explanation was required for why God's chosen people were being subjected to the domination of evil princes and terrestrial powers. Why were so many bad things happening? The drama of the Partzufim became a metaphysical pre-history that defined the world we live in, and set the stage for the dramas of the present, in which human beings are not just inhabitants of a divine universe, but actors. This was a revolutionary shift in perspective.  The gnostic aspects of the Partzufim have been observed by a number of scholars. They are apparent in the Zohar, and glaringly obvious in Luria's elaborations. There is a remote "true" God (Arik Anpin), a divine pleroma of syzygies (complementary male-female pairs), a cosmic catastrophe (death of the Kings/shevirah), a demiurgic figure (Ze'ir), upper and lower female archetypes (Malkhut/Binah), a female figure (Nukva/Shekhinah)

exiled in the domain of evil, and a redemptive relationship. The

redemptive relationship in early Christian gnosticism is between Christ

and Sophia; in Luria's system it is Ze'ir and Nukvah. Luria makes extensive use of the story of Jacob (who corresponds to Tiferet/Ze'ir), his two wives Rachel and Leah (right), and father-in-law Laban, to understand cosmic dynamics. The gnostic aspects of the Partzufim have been observed by a number of scholars. They are apparent in the Zohar, and glaringly obvious in Luria's elaborations. There is a remote "true" God (Arik Anpin), a divine pleroma of syzygies (complementary male-female pairs), a cosmic catastrophe (death of the Kings/shevirah), a demiurgic figure (Ze'ir), upper and lower female archetypes (Malkhut/Binah), a female figure (Nukva/Shekhinah)

exiled in the domain of evil, and a redemptive relationship. The

redemptive relationship in early Christian gnosticism is between Christ

and Sophia; in Luria's system it is Ze'ir and Nukvah. Luria makes extensive use of the story of Jacob (who corresponds to Tiferet/Ze'ir), his two wives Rachel and Leah (right), and father-in-law Laban, to understand cosmic dynamics. Despite scholarly investigations, no link to the gnosticism of late antiquity has been uncovered, and we appear to be dealing with genuine archetypes. It is worth noting the apparently spontaneous gnostic drama of Albion and his emanation/syzygy Jerusalem in William Blake's poetic prophecy Jerusalem. The notion of the divine in the Zohar has the structure of a trinity. With a certain amount of determination one can discern in the figure of Arik Anpin, God the Father; in Ze'ir Anpin, the Son; and in the figure of Nukva/Shekhinah, the Holy Ghost. This was very exciting for the Christian kabbalists of the Renaissance, who wet their breeches at this discovery. It meant that Kabbalah proclaimed the truth of Christianity! This distortion became another weapon in the arsenal of those seeking to pressure Jews into converting. It is worth noting that so-called "Christian Kabbalah" is much more a reversion to the ideas of Christian gnosticism of late-antiquity, using the structure of Partzufim to recover ancient archetypes that are detailed in 20th century discoveries such as the Nag Hammadi documents. |