|

|

|

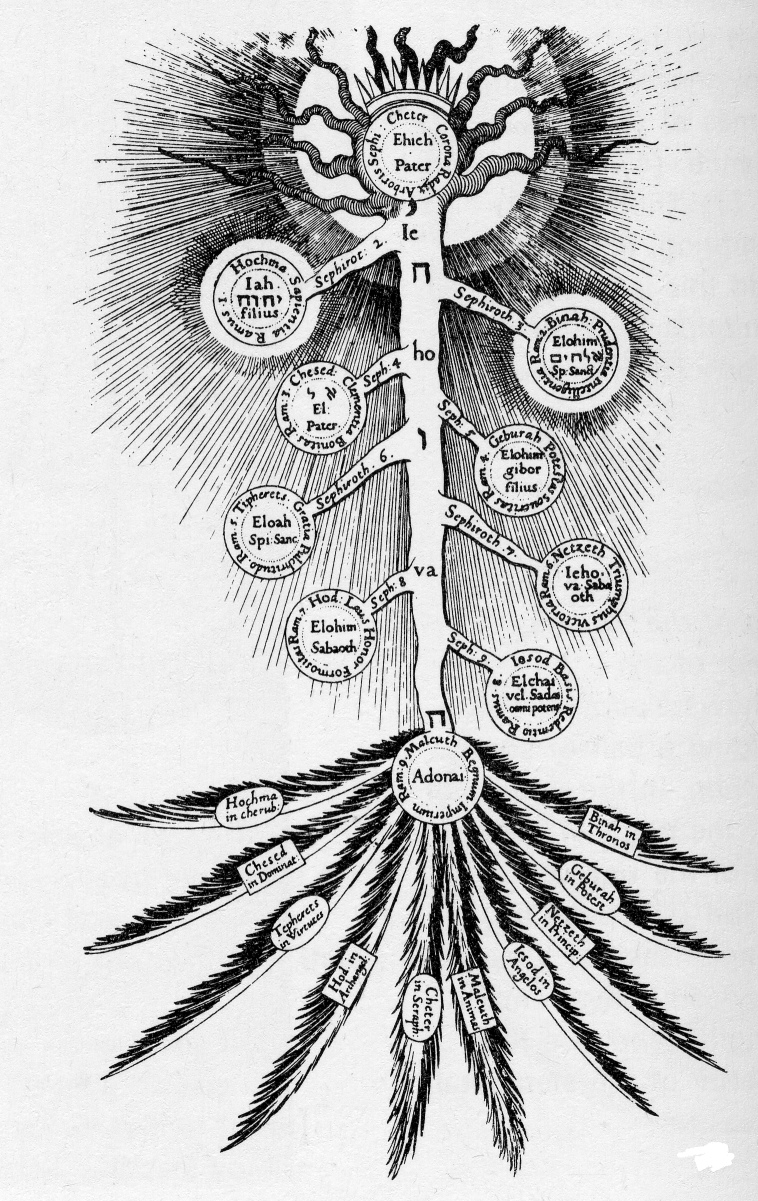

The Tree of LifeMost brief explanations of Kabbalah begin and end with the Tree of Life. The sephiroth are enumerated, their names given, a convenient illustration is provided, and some explanation is attempted. Almost nothing of value is communicated, and most people will come away mystified. The Tree of Life is most emphatically not a ladder of lights shining like a stained glass window in the sun - anyone trying to find this pretty picture in any of the early classics of Kabbalah will come away mystified. Tishby, attempting to elucidate this confusion in his commentary to the Zohar puts it very well:"It is clear from the passage just quoted that the sephirot, which are finite and measurable, are not, however, static objects, like fixed, solid rungs on the ladder of the progressive revelation of the divine attributes. They are on the contrary, dynamic forces, ascending and descending, and extending themselves within the area of the Godhead. This dynamism is found both in their hidden existence, which is oriented upwards towards En-Sof, and also in their association with the lower world, as forces of creation and direction of the universe. They are in continuous motion, involved in innumerable processes of interweaving, interlinking, and union. Even their order changes as a result of their internal movement, and "their end is fastened into their beginning". The lower sephirot elevate themselves in their yearning to return and cleave to their source, and the upper sephirot move downwards in order to give sustenance to the lower, and to transmit divine influences to the worlds below." Tishby also observes that the Zohar hardly ever uses the term sefirot:"Instead we have a whole string of names: "levels", "powers", "sides" or "areas", "worlds", "firmaments", "pillars", "lights", "colours", "days", "streams", "garments", "crowns" and others. Each term designates a particular facet of the nature or work of the sephirot." Indeed, visual depictions of the Tree are hard to find. One of the earliest images comes from the Portae Lucis of Paolo Riccio, a Latin translation of Gikatilla's Gates of Light. It is rather vague. The classic image known to so many appears in the Oedipus Aegyptiacus of Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit priest, published in the middle of the 17th. century, four hundred years after the first kabbalists began writing. The diagram of the Tree used by modern Jewish Kabbalists is usually based on the diagram published in the print edition of Cordovero's Pardes Rimonim, published in Cracow in 1591, and sometimes called the "Safed Tree".

The historic lack of imagery is all the more startling given the modern tendency to begin and end with the diagram of the Tree of Life. This may have something to do with the Biblical prohibition on images, but almost certainly something to do with the perplexing fluidity of kabbalistic writing. Many readers will be looking for clarity and consistency, and will adopt a disjunctive view of conflicting metaphors and explanations: this OR this OR this. Kabbalists tend to have a conjunctive view: this AND this AND this, even when views appear to conflict. It is useful to think of the Tree as a higher-dimensional construct that cannot be described from a single viewpoint. With these observations it is possible to begin to try to describe something about what the kabbalistic Tree of Life actually signifies. The Tree of Life is a collection of views of the dynamics of the relationship between God and the Creation. It is a view because it is created by human beings. It is a collection because no single view captures the complexity of the relationship. It is dynamic because the relationship between God and the Creation is constantly changing. And the Tree provides a view of relationship, not a view of God, which kabbalists regard as unknowable, beyond any kind of imaginative or conceptual description. Most importantly, each view is of a whole, not a collection of parts. Recall always the Shema: "Hear, O Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is One". The activity of God with respect to the Creation is always that of a whole - the parts, however described, have no autonomy. The activity of God is the prototype for all activity, for anything we can describe as "living", and so the Tree of Life is also a description of the relationship of any living thing to the Creation. The activity of human beings, for example is also characterised by the Tree of Life, and as the "activity of a human being" is just another way of defining the soul, the Tree of Life describes the soul. The Tree of Life is a fractal structure that appears at every level of reality. Every element of the Tree of Life, considered as a living thing, is another Tree of Life. R. Moses Luzzatto (1707-1746) puts it concisely: "Each of these Sephirot [in the Tree] is constructed of ten Lights, each of which in turn is composed of an equal number of lights and so on ad-infinitum. When, in one of these vessels only a single light is illuminated it is called a sephira. When all ten lights are illuminated it is defined as a Partzuf (Person)." The recursive similarity of all levels of created existence leads to an additional complication: kabbalists have a tendency to flip between differing levels of description, so that one paragraph may use descriptive elements from the Tree to refer to the activity of God, another to the soul and its response.The basic skeleton for the Tree of Life comes from an ancient document that is often beautiful and poetic in its engimatic brevity: the Sepher Yetzirah. The Sepher Yetzirah describes how God created the universe using number, language and speech: "With thirty-two mystical paths of Wisdom engraved Yah, YHVH of Hosts, God of Israel, the Living God, God Almighty, high and exalted, dwelling in eternity on high, and his name is Holy, and he created His universe with three books, with text, with number, and with communication. They are Ten Sephirot of Nothingness and twenty-two foundation letters." The Sepher Yetzirah was almost certainly a work of Hebrew Neopythagoreanism composed in the Hellenistic Middle East in late antiquity, but it was the seed for highly original readings in the atmosphere of southern Europe during the Middle Ages. The ten sephiroth of the Sepher Yetzirah became ten emanations of the divine, and the 22 Hebrew letters, divided by the SY into 3 mothers, 7 doubles, and 12 elemental (based on Hellenistic cosmology), provides the framework of the Tree of 3 horizontal paths, 7 vertical paths, and 12 diagonal paths.

The ten sefirot are

View - A Chain of EmanationThis view, which shares much with Neoplatonism, has the sephiroth forming a causal chain, so that Kether is the cause of Chokhmah, which is the cause of Binah, which is the cause of Chesed, and so on down to Malkut. Each sephira "contains" all subsequent sephira in a latent, undifferentiated form, in much the same way as an acorn contains an oak tree, so that Binah contains the dual qualities of mercy and strict judgement as possibilities that do not differentiate and manifest until the sefirot of Chesed and Gevurah. The causal-chain

ordering of the sefirot

is sometimes called the "lightning flash" order. It is characterised by

increasing differentiation, reification and structure, and what in

Neoplatonism is called alienation,

but in Kabbalah would be better termed attenuation.

The sense is that the pure light of divinity is progressively

attenuated. One of the common metaphors is a succession of veils, where

each sefira

in the causal chain veils the light of the previous sefira, so that the

light is progressively diminished until one reaches Malkut,

at which point it is almost completely obscured. Cordovero gives the

example of a craftsman who places a crucible in a furnace. The heat is

too fierce, so he places a second crucible within the first, and then a

third within the second, and so on. Each crucible attentuates the

furnace, until finally conditions are reached that support the

creation. This metaphor suggests that the sephirot can be represented

like the layers of an onion, and Cordovero provides a calligraphic

depiction of this (see diagram right), using the first letter of each

sefira as a

"layer". The causal-chain

ordering of the sefirot

is sometimes called the "lightning flash" order. It is characterised by

increasing differentiation, reification and structure, and what in

Neoplatonism is called alienation,

but in Kabbalah would be better termed attenuation.

The sense is that the pure light of divinity is progressively

attenuated. One of the common metaphors is a succession of veils, where

each sefira

in the causal chain veils the light of the previous sefira, so that the

light is progressively diminished until one reaches Malkut,

at which point it is almost completely obscured. Cordovero gives the

example of a craftsman who places a crucible in a furnace. The heat is

too fierce, so he places a second crucible within the first, and then a

third within the second, and so on. Each crucible attentuates the

furnace, until finally conditions are reached that support the

creation. This metaphor suggests that the sephirot can be represented

like the layers of an onion, and Cordovero provides a calligraphic

depiction of this (see diagram right), using the first letter of each

sefira as a

"layer".

Viewing the sefirot as an emanatory chain suggests that there is a top (Keter) and a bottom (Malkhut). Neoplatonic emanatory schemes certainly do have a top and a bottom, with the One, or the Good at the top, and Matter at the bottom. Matter is seen as a negative, as an absence, completely lacking in form or being, but it is still necessary to receive the imprint of form, like clay in a mould. Kabbalah avoids this difficult and unsatisfactory dualism by connecting Keter and Malkhut. Cordovero was well aware of the potential difficulty, and references a well-known verse from the Sepher Yetzirah:  ""Ten sephirot without substance, the beginning is fixed in the end, and the end is in the beginning etc". The Master is one and there is no other, and what do you count before one? Although the sefirot are ten in relation to the changing aspects, the end is fixed in the beginning. The head is the end, and the end is the head, for they are part of God's single substance. God is one with them and - God forbid - there is no duality." In Kabbalah the Neoplatonic concept of Matter is missing. Its place is taken by Din, the abstract quality that defines and determines, and sets boundaries and limits on things. One can think of it as form or constraint. A way to imagine this is to picture a ball moving in space. If we confine it in a box, it has less space to move in. If we flatten the box, it can only roll in two dimensions. If we make the box small enough, it cannot move at all. In an abstract sense the ball is being increasingly constrained; ball-and-box together express the information or degrees of freedom possible in the system. Another example would be the rules of a game such as chess, that define how pieces can move. The rules constrain the freedom of the pieces. Malkhut is the final expression of rules and constraints that make the emergence of life possible.View - The Names of God An

important view

of the sefirot

is that they represent the executive power of the Names of God. That

is, the power of God manifests through His Names, and the nature of a

sefira is essentially identical with the power of a Name. One of the

most popular works of Kabbalah, translated into Latin in 1516 by a

German Jewish convert Paolo

Riccio, is Gikatilla's Gates of Light.

This work is a series of essays on the divine Names associated with

each of ten Spheres or Gates. Gikatilla justifies these attributions by

extensive quotation and interpretation of verses drawn from canonical

literature, mainly the Bible, and it is obvious Gikatilla is collating

views from an established tradition. His attributions have remained

largely unchanged to the current period. The Names given by Gikatilla

(see diagram right) are: An

important view

of the sefirot

is that they represent the executive power of the Names of God. That

is, the power of God manifests through His Names, and the nature of a

sefira is essentially identical with the power of a Name. One of the

most popular works of Kabbalah, translated into Latin in 1516 by a

German Jewish convert Paolo

Riccio, is Gikatilla's Gates of Light.

This work is a series of essays on the divine Names associated with

each of ten Spheres or Gates. Gikatilla justifies these attributions by

extensive quotation and interpretation of verses drawn from canonical

literature, mainly the Bible, and it is obvious Gikatilla is collating

views from an established tradition. His attributions have remained

largely unchanged to the current period. The Names given by Gikatilla

(see diagram right) are:

Many

Hermetic Kabbalists use minor

variants of the Names. These

variants have a long history, dating back to the late renaissance, and

can be found in Cornelius Agrippa's Three

Books. See also Robert

Fludd's Tree of Life diagram (right). Many

Hermetic Kabbalists use minor

variants of the Names. These

variants have a long history, dating back to the late renaissance, and

can be found in Cornelius Agrippa's Three

Books. See also Robert

Fludd's Tree of Life diagram (right).

View - The Divine King"Earthly kingdoms are like the kingdom of Heaven" - Mishnah  Many

European cathedrals

contain statues of kings sitting in state; that is, wearing a crown,

and holding formal regalia - sword, sceptre, orb etc. Christ is often

depicted as King in a similar way, sitting in his glory, surrounded by

ranks of saints and angels. Many

European cathedrals

contain statues of kings sitting in state; that is, wearing a crown,

and holding formal regalia - sword, sceptre, orb etc. Christ is often

depicted as King in a similar way, sitting in his glory, surrounded by

ranks of saints and angels.This imagery is of great antiquity. God is depicted in the Bible as King; as Arthur Green (in Keter) comments: "The kingship of God is a central theme of the Hebrew Bible, and kingship is probably the most widespread single metaphor used to describe the relationship of God, His Creation, and His people." There is an important view that the Tree of Life represents a King. Keter is the Crown. Chokhmah, and Binah are cognitive functions in the brain ... but also Father and Mother to the King. Chesed is the right arm of authority and benevolance (sceptre) and Gevurah is the left arm of justice and retribution (sword). Tipheret is the King. Netzach and Hod are the legs, and also the hosts/armies (tzabaot) of the King. Yesod is the phallus. Malkut is simultaneously the Kingdom, and the Queen, beloved of the King (see the Song of Songs and Partzufim). Malkut might also be considered as the throne.To a considerable extent this image of God as King is conflated with the image of the gigantic Primordial Adam (Adam Kadmon), the Partzufim, and also any human being considered as regent to the Creation. View - PartzufimThe Partzufim are divine archetypes overlayed and integrated into the Tree of Life. This is a complex topic and is discussed elsewhere.See Partzufim. View - OrganismA view that is expressed in the Zohar, and frequently repeated, is the need for the divine "lights" and "receptacles" that constitute the sefirot to find a "balanced configuration". This is a configuration in which each sefira receives light in proportion to its capacity to receive it, and exchanges light with other sefirot in proportion to their ability to receive and transmit. This is not a given; there is an old midrash that God created many worlds and destroyed them. The Zohar interprets this as prior creations in which the sefirot failed to achieve a balanced configuration. R. Isaac Luria developed this idea into shevirah, the Shattering of the Vessels.The issue is the dynamic equilibrium between the powers of chesed and din, light and dark. Too much chesed and the receptacles cannot bear it; too much din and we have what T.S. Eliot describes as "paralyzed force, gesture without motion", the Tree of Death. The middle pillar of the Tree represents the dynamic equilibrium between these tendencies. Since R. Isaac Luria there has been a tendency to apply the Tree of Life at every level of reality. Every functioning microcosm can be described by a balanced configuration of sefirot. There is a kabbalistic holographic principle that finds a Tree in every sefirot, so that reality can be decomposed at every level into the same, fractal, self-similar structure ... not unlike a real tree, where every part has the same branching structure as the whole. This is one way to think about the statement in the Sepher Yetzirah that their "end is in their beginning and their beginning is in their end" - at every level one finds the same structure and dynamic. This is an economy of means that is widely observed throughout the natural world, and a reason why fractal generators (e.g. Apophysis) are so successful at generating complex, organic forms. According to this view, the Tree of Life is an abstract template of organism, any kind of organism: a carbon atom, an amoeba, the human psyche, society, the organism of God. Anywhere one finds a whole composed of a defined, dynamic equilibrium of parts, one finds a Tree of Life. It comes as no surprise that ideas of such scope and generality have been discussed outside of Kabbalah. The thinker Arthur Koestler, studying the emergence of complex systems, defined a holon as an autonomous whole that is itself composed of holons, and is capable of becoming a part of a larger holon. For example, atoms are holons that can become parts of molecules, which are holons that can become parts of proteins, which can become parts of cells, which can become parts of organs ... and so on.

The Tree of Life as a Holon Holons can become, via communion, part of larger holons: this is transcendence. Something new has emerged that is greater than the sum of the parts. A holon may lose its internal coherence and fall apart into its constituent holons: this is dissolution. These ideas map onto the Tree of Life with surprising accuracy. The left-hand pillar, embodying the principle of din, corresponds to agency. The right-hand pillar, embodying the principle of chesed, corresponds to communion. The middle pillar corresponds to homeostasis at the centre: upwards it corresponds to transendence, downwards to dissolution (or alternatively, embodiment via lower-level holons). An extensive discussion of holons and their relation to an integral worldview can be found in Ken Wilber's Sex, Ecology, Spirituality. View - Metaphysical DovecotIn his massive survey of Renaissance occult philosophy, Cornelius Agrippa provides tables of correspondences - "scales" - for all the numbers up to twelve. His scale of the number ten is essentially a table of correspondences for the sefira of the Tree of Life - divine names, angel orders, archangels, planets, animals, parts of the body and shells. This approach goes back to the various tables that can be constructed out of the Sepher Yetzirah. There is also a close relationship to the ancient hermetic notion of sympathies, the idea that certain things have an underlying sympathetic or harmonic connection via a higher world of the planetary or divine essences.Since the time of Agrippa these tables have grown. The modern Hermetic Kabbalist is likely to encounter them in works such as Mather's introduction to the Kabbalah Unveiled, Gareth Knight's A Practical Guide to Qabalistic Symbolism, Dion Fortune's The Mystical Qabalah, and Aleister Crowley's amendation of Golden Dawn teaching material, Liber 777. Because many modern students of Hermetic Kabbalah tend to learn about the sefirot ground-up from these lists, there is a view that the Tree of Life is a kind of metaphysical dovecot in which related ideas roost and synergise together. A negative consequence of a preoccupation with lists and tables is their lack of subtlety. It is difficult to merge two differing tables, which leads to a confusing and inclusive (but functionally useless) metatable, or a schismatic tendency amongst table holders. Debates about correspondences occur with great frequency on forums, and tend to be reminscent of the popular song: You like potato

and I like potahto, View - Days of Creation

|